The Courant article soon stirred up a hornet’s nest. The College Committee met and, as it wished to have the matter resolved as quickly and quietly as possible, Robertson Smith was asked to apologise and publish a recantation. This he refused to do and a year later, at the May General Assembly of 1877 – for the wheels of the Presbytery turned very slowly – he demanded that formal charges (a “libel” in church law) be laid against him so that he might defend himself adequately against the imputation of heresy. This resulted in his lectureship being temporarily withdrawn. Fundamental hotheads of those in favour of a heresy trial were Dr James Begg, a man of uncompromising Presbyterian orthodoxy, and Sir Henry Wellwood Moncreiff, leader of the so called Highland Horde and an eminent Free Church expert in ecclesiastical law. It was the latter’s request to keep up the banner of the righteous. Robert Rainy, Principal of the Edinburgh Free Church College, initially avoided taking sides and made genuine efforts to reach a compromise but ultimately was to withdraw his support from Robertson Smith.

The Heresy Trial

Initially, there was little reaction to the publication of the “bible” article. Then, in April 1876, an anonymous review was printed in The Edinburgh Courant, the author of which expressed his worst fears for the spiritual welfare of those members of the public who might now freely read such views as Robertson Smith had expressed. The writer, generally acknowledged to be Dr A. H. Charteris, professor of Church History at Edinburgh University, was a highly orthodox member of the established church. At the time, Robertson Smith together with his friend, the painter George Reid, unsuspecting were on a journey through the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. Together they kept an illustrated travel-diary which later came to be printed in a private edition as Notes and Sketches. Accompanying the pair were Robertson Smith’s two youngest sisters, Alice and Lucy, who were to stay in Germany to complete their education.

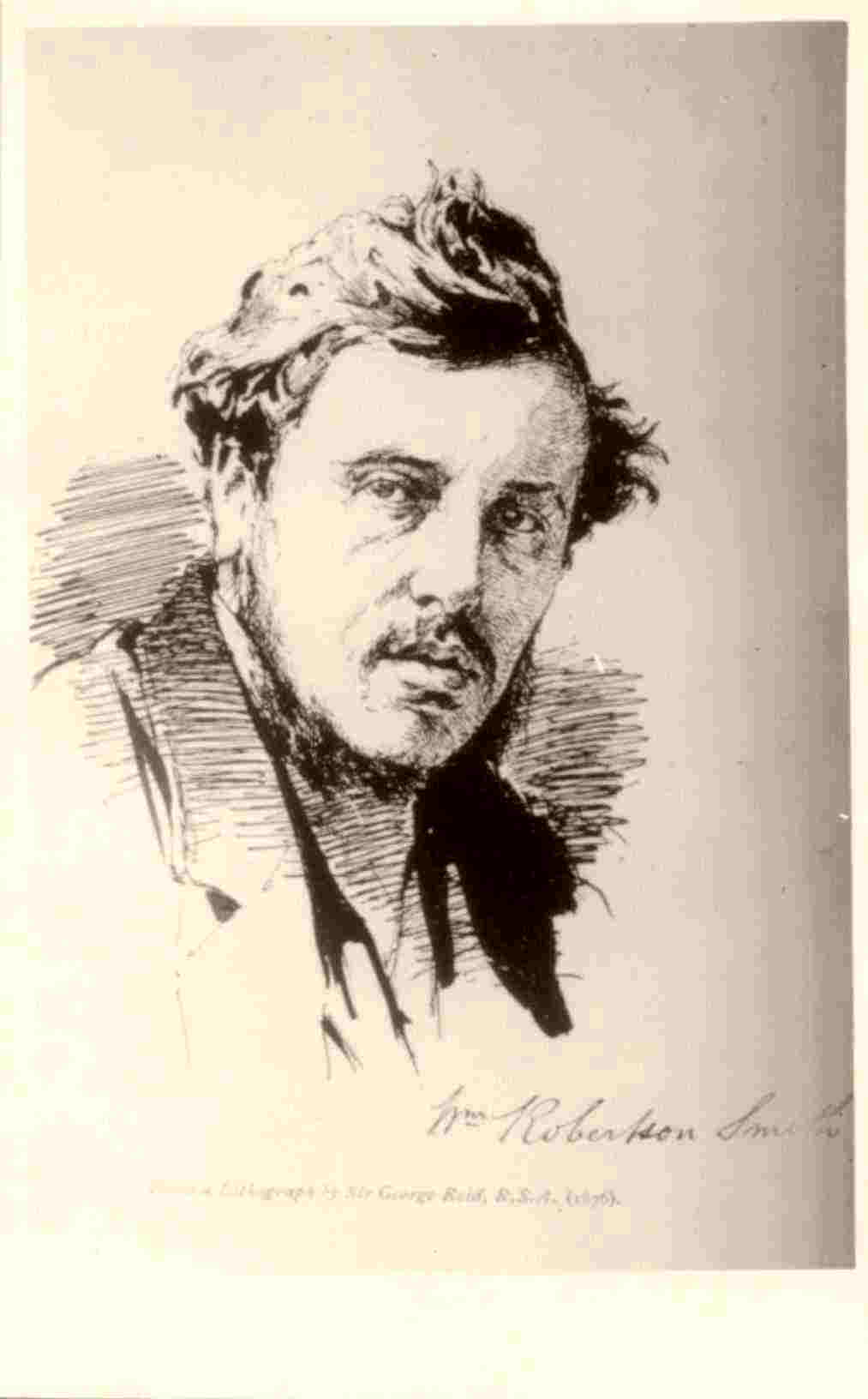

William Robertson Smith, George Reid, 1876, FP

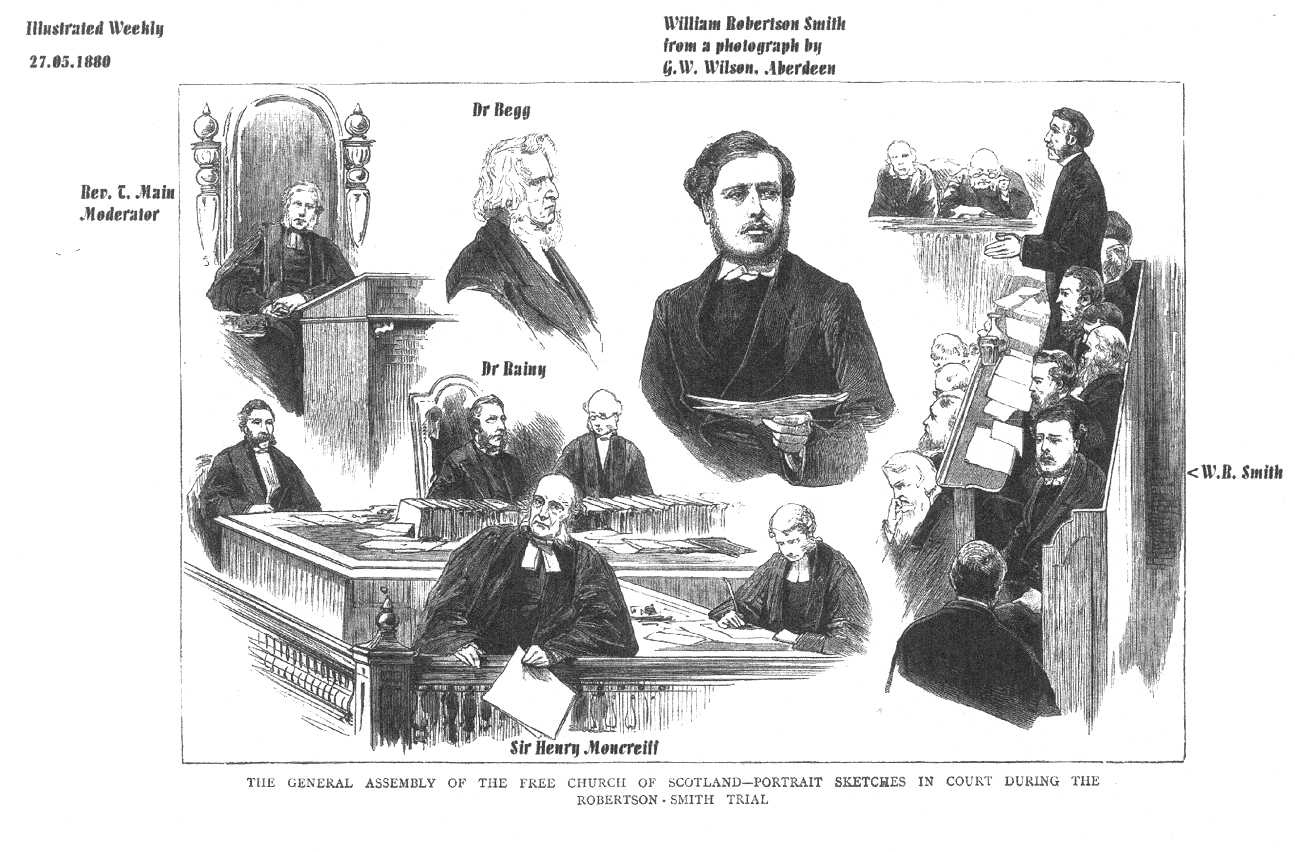

Illustrated Weekly, 27.05.1880, Sketch

Apart from the general charge of expressing “unsettling” opinions which cast doubt on the divine authority and inspired character of the Bible, eight separate counts laid against Robertson Smith, all relating to his expressed views on the biblical text. After lengthy preparation the first public trial was held at the Free Church General Assembly - supposed in Glasgow - during May, 1878. A large audience was present in view of the enormous level of public interest in the affair. No decision was made, however, and the case dragged on. Though popular opinion, be it minister, be it flock, seemed to be strongly on the side of Robertson Smith, the more conservative members of the Free Church had no intention of conceding defeat and repeatedly postponed any final, definitive vote. One by one, the specific counts were dropped until only that relating to the date and authorship of Deuteronomy remained. Finally, after three years on May 25, 1880, the Assembly formally cleared Robertson Smith of heresy but agreed that he should be cautioned to abstain in future from expressing “incautious or incomplete public statements”.

Nevertheless, peace was to reign only briefly within the Free Church. Soon after this apparent victory for the Robertson Smith cause, the next volume of EB9 was released from the printing press. It contained a further article from Robertson Smith’s pen, “Hebrew Language and Literature”, which confirmed the author’s unchanged critical view concerning the history of the origins of the Old Testament. This was to prove simply too much for the orthodox believer. The young professor was accused of dishonesty, irrespective of the fact that the new volume had been prepared for printing well before the conclusion of the trial. After an Assembly debate in 1881, Robertson Smith was dismissed at the end of May from his professorial chair at the Free Church College of Aberdeen.

If that verdict and the loss of his teaching work seemed to represent complete defeat for Robertson Smith, subsequent history was to demonstrate that the true victory was his. By the end of the century, the principles of biblical “higher criticism” were fully accepted by virtually all British theologians and their findings freely communicated. Even within the Free Church itself there came a more liberal view of such matters. Greater freedom of expression was allowed in both pulpit and college lecture rooms, without detriment to religious faith. And, one might add, the Scots people felt rather proud of their young, brilliant fellow-countryman whose sharp mind and polished argument had enabled him to stand firm against the weight of the clerical establishment.

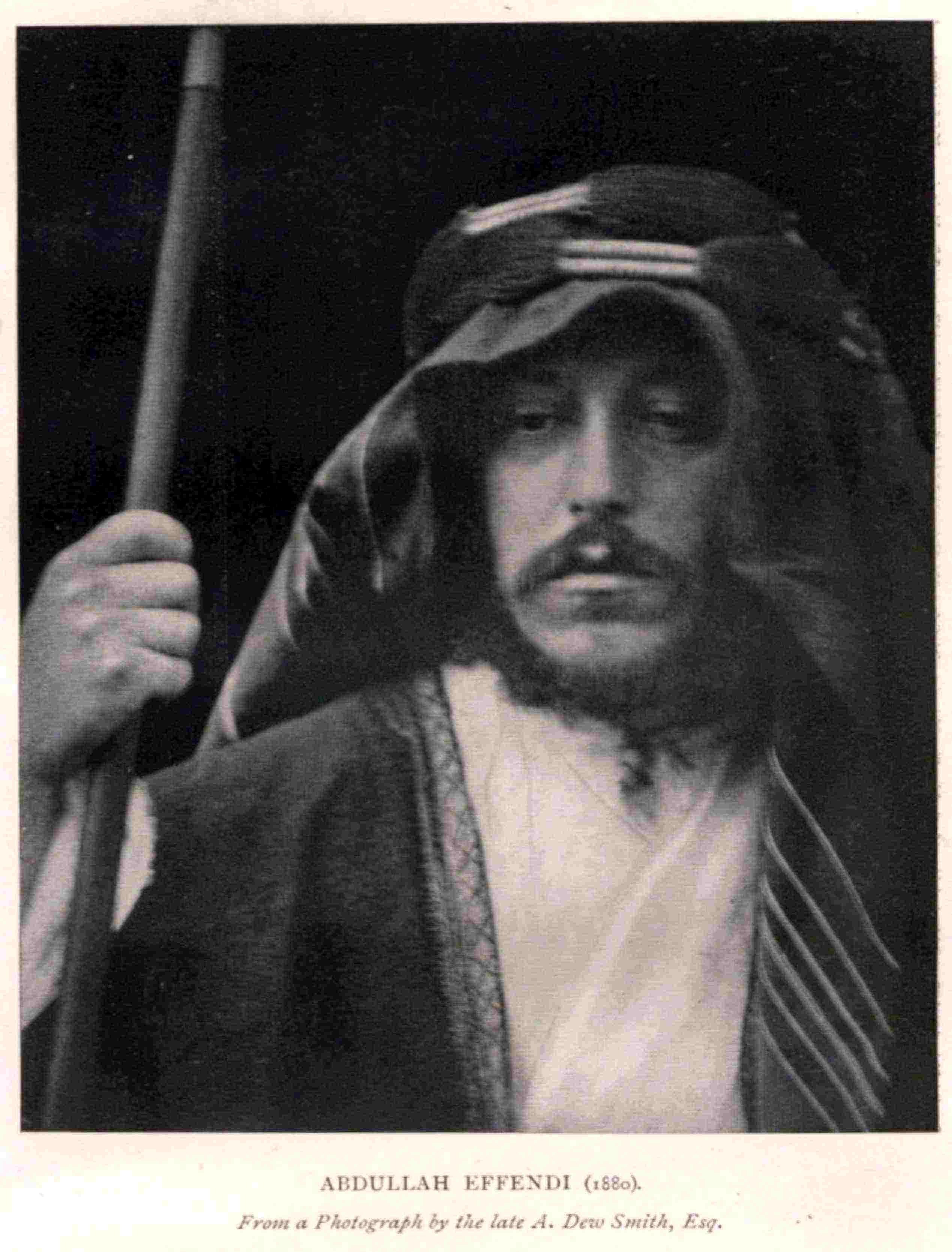

Free from the duties of his chair, Robertson Smith had undertaken several journeys to the Near East during the protracted trial. The winters of 1878/79 and 1879/80 saw him in Egypt, Palestine and the Arabian Peninsula where he quickly grew familiar with the language and culture of a people whose origins and traditions fascinated him. He visited ancient sites and deciphered inscriptions. With his ready skill in acquiring Arabic, he was to relate easily to people of all kinds. At first he followed the usual tourist routes but soon penetrated deeper into the Arab world which was barely known to westerners at that time. On his second journey, he secured permission from the Emir of Mecca to travel from Jeddah to Taîf crossing the holy district around the pilgrimage places, in appropriate garb – a burnous.

Abdulla Effendi, 1880, B&C

During the first months of 1881 Robertson Smith delivered on invitation of sympathetic friends within the Free Church a series of extremely popular and well-attended public lectures in both Edinburgh and Glasgow on bible criticism in relation to the Old Testament. These were rapidly published in book form under the title The Old Testament in the Jewish Church (second edition in 1895, translated into German in 1894) and formed his first authoritative publication in this field.

A year later, following a second, equally successful lecture series, The Prophets of Israel and their Place in History to the Close of the Eighth Century B. C. was published (second edition in 1895, more editions until now). Thereafter Robertson Smith’s interest was to turn increasingly to the field of comparative religion.