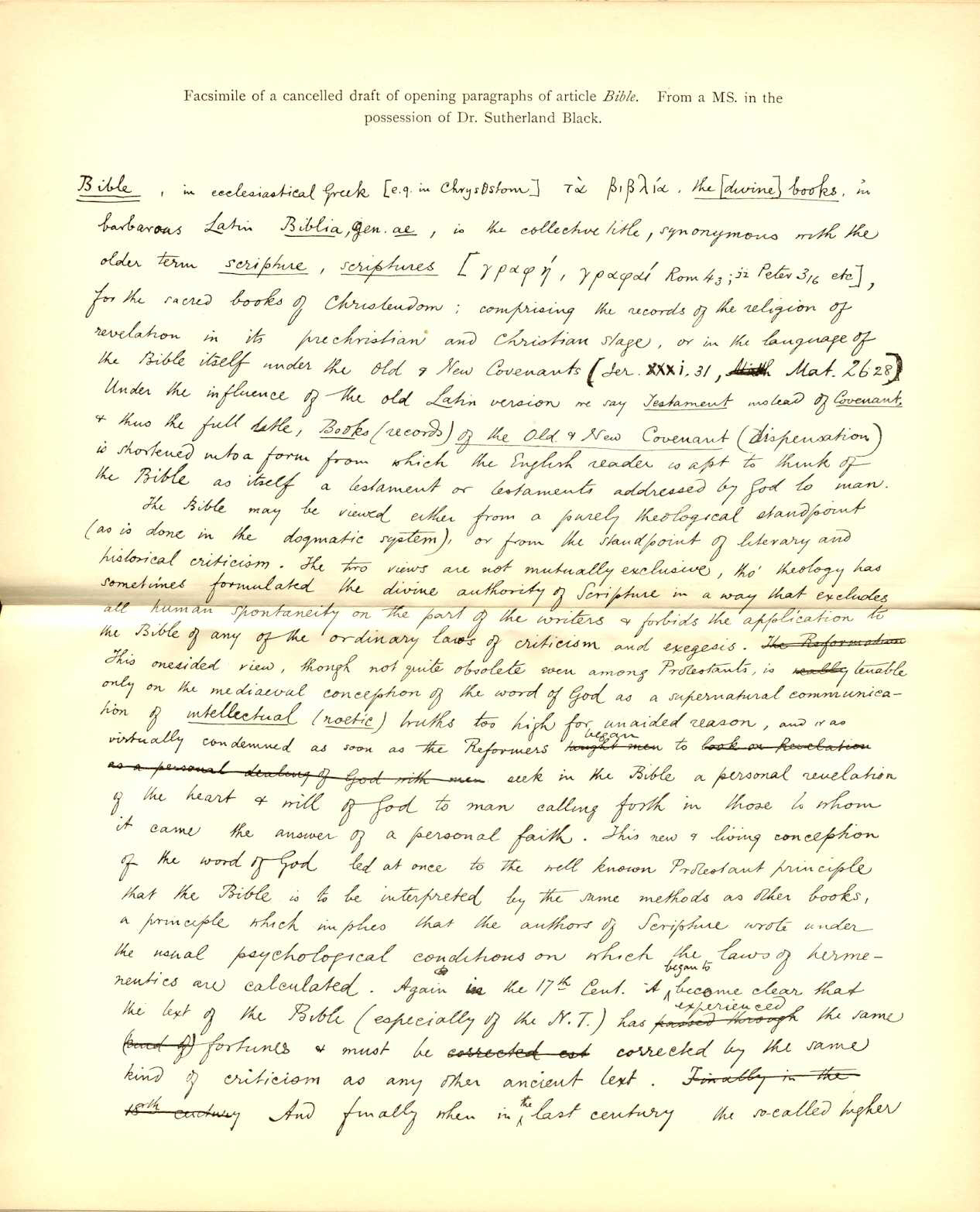

In Edinburgh, Andrew Bruce Davidson, professor of Hebrew at New College, early left his mark on Robertson Smith’s thinking. From Davidson’s teaching he grasped the conviction that the Bible was to be regarded as a man-made record of divine revelation, to be read critically just as one would approach any other historical document. In the Scotland of that day, such an approach was generally accepted as valid by many scholars but was not considered suitable for communication to lay members of the church.

Robertson Smith’s emerging interest in the development and psychology of religion was further influenced by his meeting with a fellow Scot in Edinburgh, John F. McLennan, who was one of the first to propose the notion of an evolutionary development of religion progressing from animism and totemism towards an ultimately monotheistic concept of divinity.