Having been recruited by Baynes to be co-editor of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (the so-called scholarly edition) Robertson Smith left Aberdeen and took up residence in summer 1881 in Edinburgh along with his youngest brother, Herbert. The work was congenial to him and by no means onerous but other demands were to be made on him during the following years.

Edinburgh and Cambridge

Herbert Smith, 1880s, FP

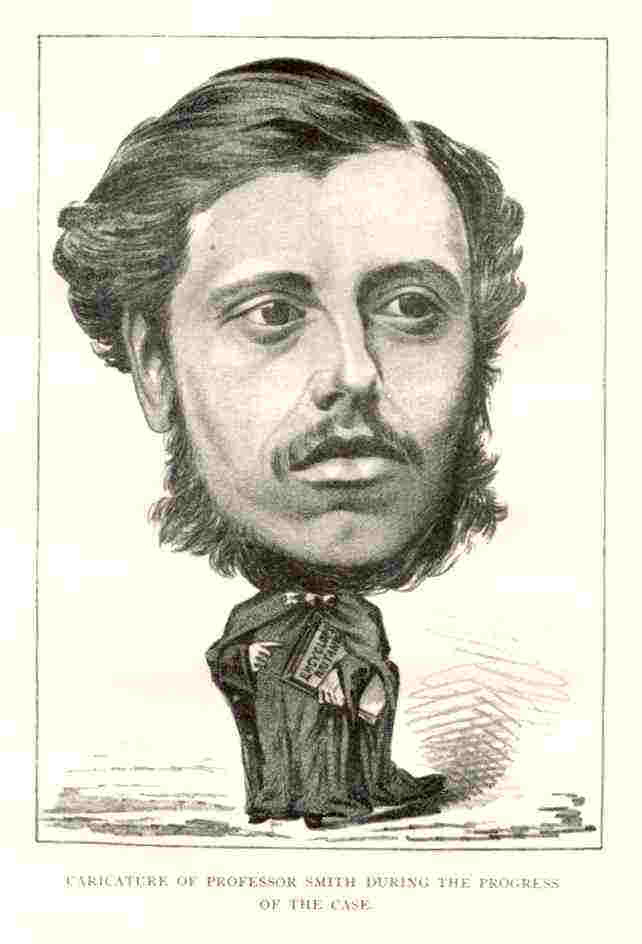

Caricature, B&C

Yet Robertson Smith’s stay in Scotland was only to be of limited duration. When in 1882 Professor Palmer, Reader of Arabic at Cambridge University, was murdered in Palestine, Robertson Smith was encouraged by William Wright, Professor of Arabic at Cambridge and already a close associate, to apply for the vacant position. A campaign similar to that of 1869/70 brought success and early in 1883 Robertson Smith moved into rooms at Trinity College Cambridge, ultimately becoming a fellow of Christ’s College from 1885.

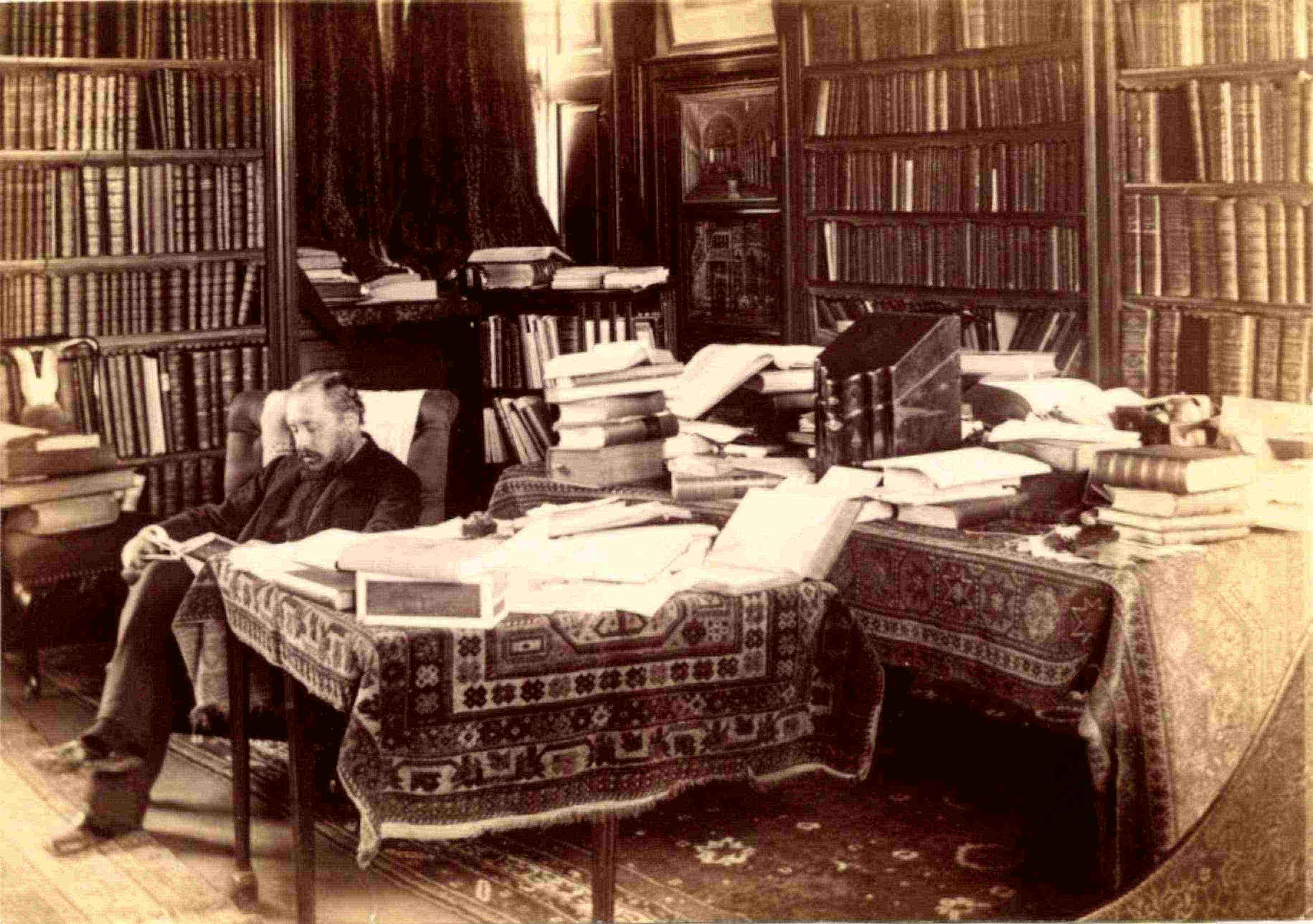

From Cambridge he continued his editorial work for the EB9, which involved an immense amount of correspondence with contributors worldwide. Robertson Smith himself wrote innumerable articles, both signed and unsigned. With justification he could later claim to have been the only person to have read every word of the entire contents of the ninth edition. After Baynes’ death in 1887, Robertson Smith became editor-in-chief, still supported loyally by his Edinburgh colleague J. S. Black. In 1888 the last of the twenty-five volumes was completed and a large banquet was held in Christ’s College in honour of the occasion.

Robertson Smith’s main area of study lay in the general field of comparative religion, from which flowed his increasing interest in anthropology, ethnology, sociology and psychology, as his correspondence with biblical scholars, arabists and orientalists and his publications amply illustrate. Crucially, his work explored the origins of ritual and myth, totemism and taboo, sacrifice and the associated concept of rebirth: indeed, the whole evolution of religious thinking from primitive animism up to the “enlightened” religion of the 19th century. He recognised the importance of religious practices as a means of strengthening the bonds within society and of preserving unity and harmony within the group. Ritual, in his view, became mandatory through the subsequent creation of explanatory myth, while sacrifice and the shared sacrificial meal confirmed the common bond between men and their God.

In 1885, following a series of lectures on the subject, Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia (second edition in 1903, last editions 1990) was published, dealing in great detail with pre-Islamic tribal relationships within the Arab world. Robertson Smith’s close friendship with William Wright and James George Frazer proved fruitful for all three. Wright, the orientalist, who knew the dialects of the Arab language like no other Englishman, and Frazer, encouraged by Robertson Smith, collected countless records of religious practice and myth throughout the world, each came to the same conclusion: that all religions passed through similar evolutionary stages, cultivating similar traditions – and all with the same underlying purpose.

When Henry Bradshaw died in 1886 Robertson Smith became his successor as head of the Cambridge University library. This meant an obligation which besides his lectures and the editorship of the EB9 was to challenge his strength. The sudden death of his predecessor made it all not easier for him. But as always Robertson Smith rose to the task. His work as a librarian was to be very productive and exactly what he wanted.

William Robertson Smith, ca. 1885, FP

In April 1887 the Burnett Trustees invited him to deliver, at Aberdeen, a series of public lectures on the topic of Semitic religion. The first of the three series proved an outstanding success and was published in 1889 under the title The Religion of the Semites, First Series: The Fundamental Institutions (several editions until now, translated into German in 1899). This was to become one of the classic works on comparative religion and social anthropology. Many subsequent scholars were deeply inspired by Robertson Smith’s conclusions and proceeded to pursue them – not least Sigmund Freud and Emile Durkheim.

As planned, Robertson Smith duly delivered the second and third series of Burnett Lectures but his declining health prevented their revision for publication, although a slim volume based on his original notes was eventually brought out in 1995 as Lectures on the Religion of the Semites, Second and Third Series, edited by John Day (Oxford University Press).

William Robertson Smith' study in Cambridge, ca. 1889, FP

During the summer of 1888 Robertson Smith had travelled extensively with friends through France, Spain and Italy, a relaxation which he invariably enjoyed. On this occasion he was especially interested in the relics of Moorish culture to be found in the south of Spain. That winter he presented as planned the first series of Burnett Lectures and the following spring saw him in North Africa, where the relatively unspoiled Arab culture greatly impressed him, and journeyed on to the Near East. Shortly after his return to Cambridge, his friend and mentor William Wright died and in the summer of 1889 Robertson Smith was appointed to succeed Wright in the Sir Thomas Adams Chair of Arabic.