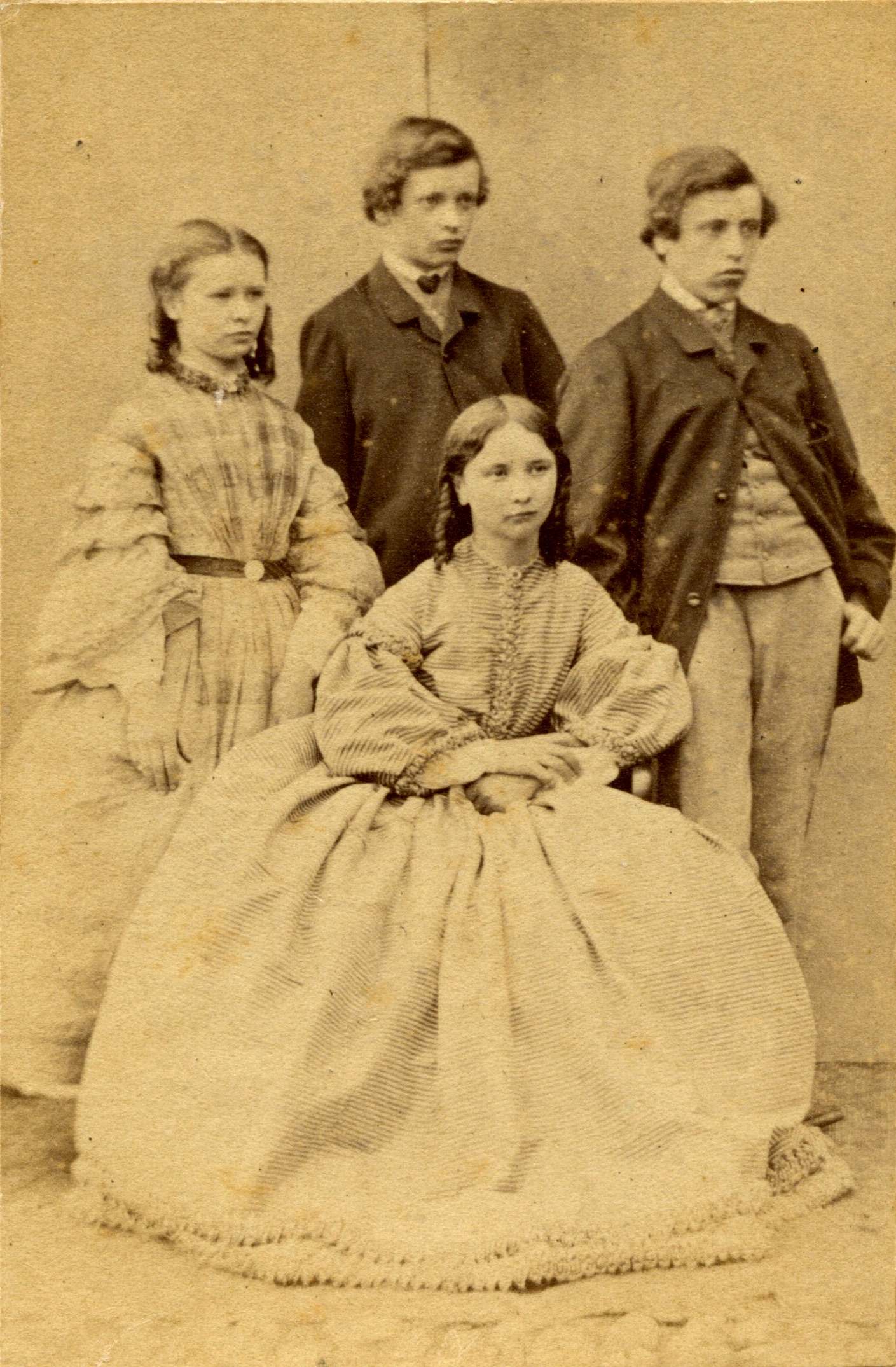

His brother George, one year younger, was also of high intelligence and had an equal thirst for knowledge. Both boys, as well as their older and equally gifted sister Mary Jane, were fortunate in possessing parents who were capable and enthusiastic teachers, willing to whet their children’s natural curiosity and to encourage free debate, not only in religious matters but in the burning topics of the day, including scientific and philosophical issues. Even Darwin’s theory of the origin of species was not a forbidden theme. The children, like their father, were linguistically talented and from an early age were schooled thoroughly in Latin, Greek and even Hebrew. As young teenagers, both William and George gained top awards in the Bursary Competition and in 1861 set off to become students at the new University of Aberdeen, formed in 1860 by the amalgamation of Marischal and King’s Colleges. William had just turned fifteen and George was only 13. They were accompanied by the two oldest of their sisters, Mary Jane and Isabella, who were to attend school in Aberdeen and also keep house for the boys.

Childhood, first Lessons and Study

William Robertson Smith, 1854, FP

As a child, Robertson Smith was precocious but very delicate in his health. Both parents often feared for his life and frequently kept him in their bedroom in order to keep a close watch on him.

George Michie Smith, FP

Mary Jane Smith, FP

Isabella Giles Smith, FP

Leaving for Aberdeen, 1861, FP

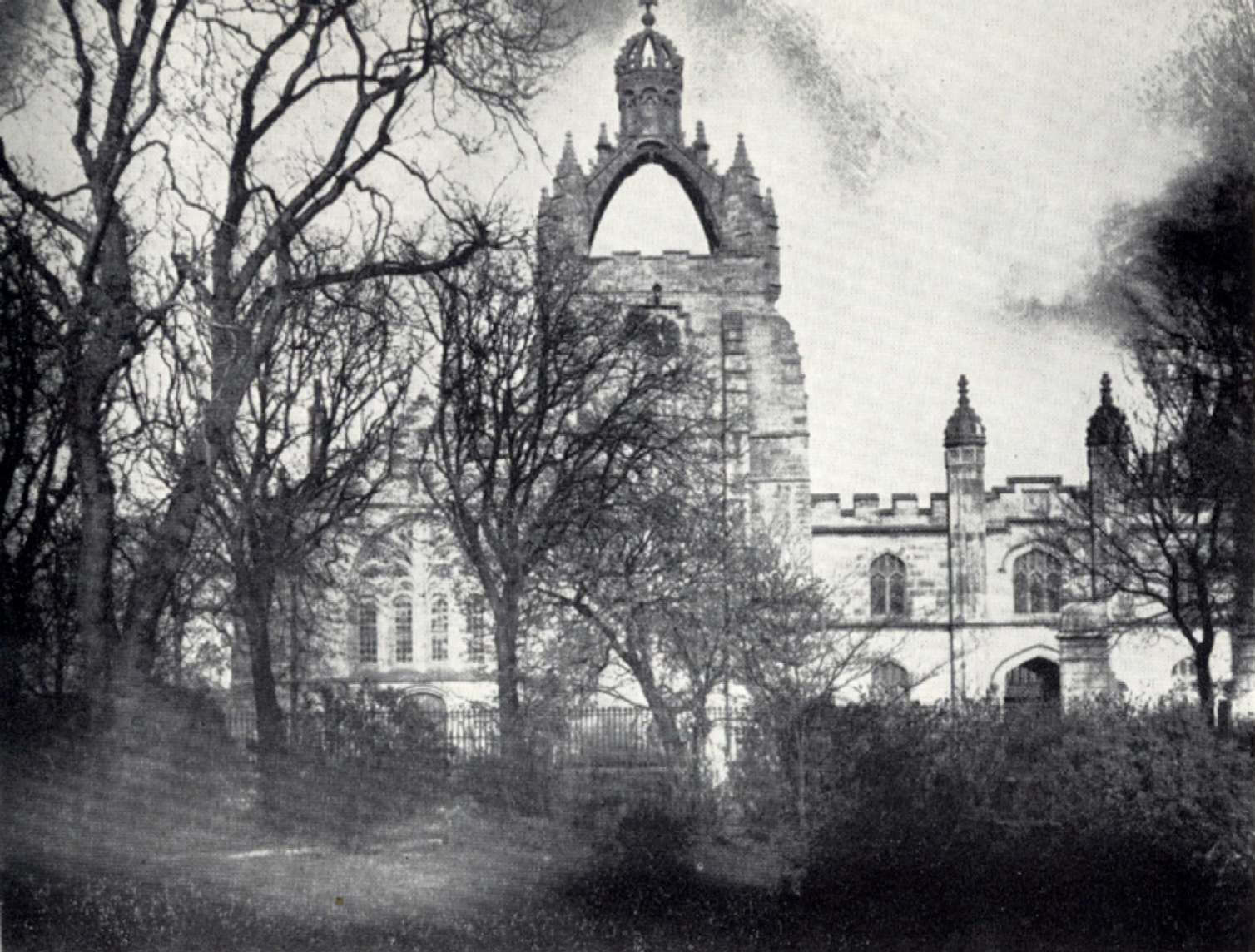

King’s College Aberdeen, 1850s, JFW

The following four years at Aberdeen were to bring academic success and distinction to both boys, threatened only by their susceptibility to that endemic scourge of the nineteenth century – tuberculosis. By special favour, Robertson Smith was permitted to take his final exams on his sickbed and gained the accolade of being awarded the Town Council medal for best student of the year. He could have entered every British University.

George, however, became so ill in 1864 that he could not be taken home. His sister Mary Jane cared for him but became infected herself and died shortly after. George recovered for a time and was able to continue with his studies, graduating finally in 1866 with high honours; but only three weeks later fell prey to the illness which had relentlessly dogged all three children.

In autumn 1866, at the age of nineteen, Robertson Smith enrolled at the Edinburgh Free Church College. Though highly gifted in science and mathematics, he had long determined to serve the Free Church as a minister. However, in addition to his theological studies, he was able to secure the post of assistant to Professor Peter G. Tait, head of the Natural Philosophy department at Edinburgh University, where one of his students was the confessedly idle Robert Louis Stevenson. Over the next four years, Robertson Smith rapidly began to produce a series of highly-regarded essays on both theological and scientific topics. It was also remarkable that he assisted Tait with what were known as the “Ladies Classes”. Women in Edinburgh had newly been permitted to attend separate lectures in certain subjects at university level and to sit exams, but not to graduate. In one report Robertson Smith stated that the best female students in the Natural Philosophy class undoubtedly reached a level of achievement comparable with that of the most able male students, although he felt that the women often hesitated to insist on their point of view even if they recognised a counter-argument as nonsense.

Free Church College Edinburgh, Playfairs Plan, NCE

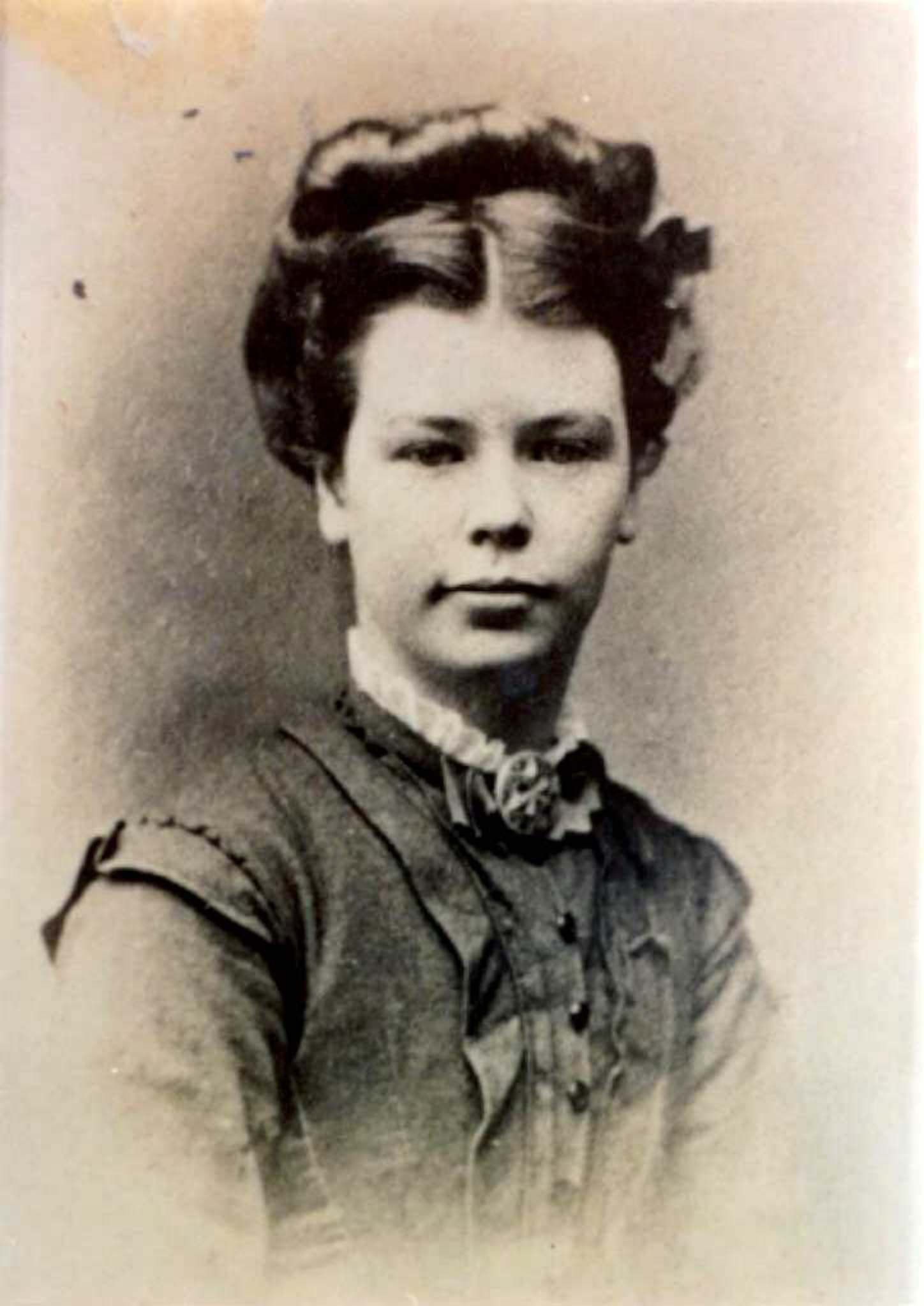

In this connection it is also characteristic that Robertson Smith ensured that his sisters should receive education beyond their more limited home schooling. During his studies at Edinburgh, both Ellen (Nellie) and Alice boarded with him for a time and attended private school and lessons. Later, with Robertson Smith’s help, Nellie spent more than a year in Göttingen taking lessons in music, drawing and languages, while Alice and the youngest sister, Lucy, were also allowed on his recommendation to spend several months in Germany.

Ellen Deans Smith, FP

Alice Smith ca. 1865, FP

Lucy Smith 1877, FP

One year ahead of Robertson Smith at New College was his fellow-student, John Sutherland Black (1846-1923), himself the son of a Free Church minister. The two were to become lifelong intimates and it was Black who, along with George W. Chrystal, was to be his friend’s biographer. Many more of Smith’s close acquaintances could be listed, amongst these being Thomas M. Lindsay, later Professor of Church History at the Glasgow Free Church College as well as Archibald McDonald whom Robertson Smith had already known as a student from his Aberdeen University days.

In the summer of 1867 Robertson Smith visited Germany for the first time. At Bonn he met (and boarded with) Carl Schaarschmidt, professor of philosophy there, attending lectures by both Schaarschmidt and Adolf Kamphausen (Old Testament). From this point, Robertson Smith’s thinking began to be decisively influenced by the radical trend in biblical criticism that was then current at most German universities.

During this and subsequent trips to Germany, he established numerous personal contacts, of whom the mathematician Felix Klein was to become a particularly close friend. Mastering the German language proved easy for him and many aspects of German life and culture strongly appealed to him.

In the course of that first stay in Germany, his father joined him for several weeks, during which time they spent some time at Bonn with the Schaarschmidts, travelled up the Rhine, visited Heidelberg and took pleasure in meeting many old and new acquaintances. It must have been quite an extraordinary experience for the old man. Later, Robertson Smith undertook another study tour of Germany in company with his friend J. S. Black. They remained several weeks in Göttingen, listening to, amongst others, the lectures of Albrecht Ritschl (theology) and Hermann Lotze (philosophy), both of whom were to influence the thinking of the young students. Who besides have amply enjoyed German student life. The young Julius Wellhausen, later the eminent orientalist, bible critic and exegete, became a close friend and colleague during this period.